classroom breakfast and health: impact on nutrition and weight

Despite being the world's richest country, the USA is home to many people with hunger and food insecurity. Public schools are on the first line of defense to fill this gap, and many offer daily free meals to students teetering close to the federal poverty line. Despite widespread breakfast programs in inner-city Philadelphia to address the close to 90% poverty rate, many students still are without breakfast on a daily basis. Experts introduced the One Healthy Breakfast initiative, which predicted that serving breakfast in the classroom alongside breakfast-specific nutrition education and local healthy-food marketing would increase students' access to breakfast and lower rates of obesity.

does providing breakfast in the classroom improve the health of students?

Source: Breakfast in the Classroom Initiative and Students’ Breakfast Consumption Behaviors: A Group Randomized Trial

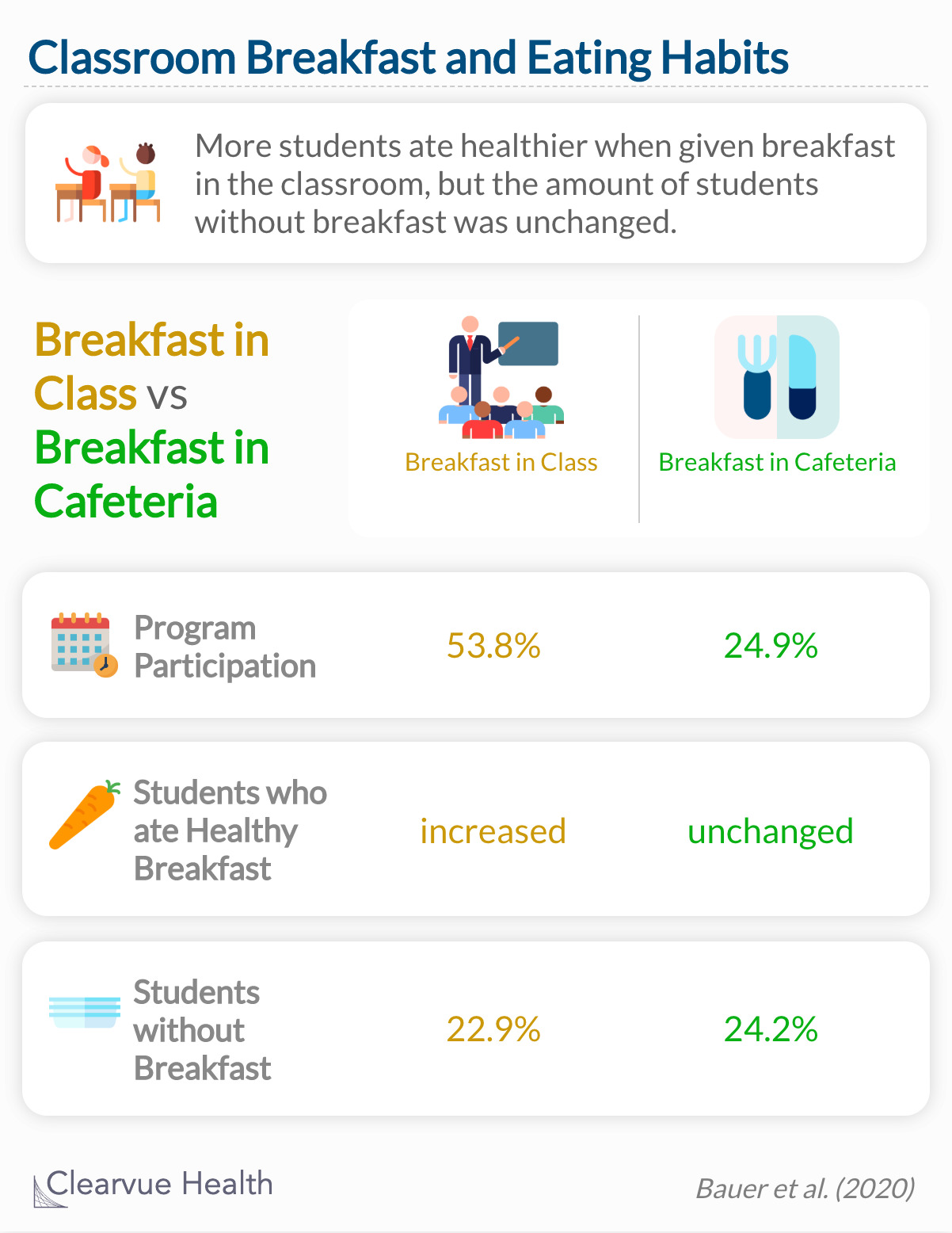

Of the 16 schools participating in the trial, 8 gave breakfast in the classroom to eligible students in grades 4 through 6, while the remainder offered their normal breakfast in the cafeteria. Breakfast-in-Classroom students were given lessons about nutrition. The effect of this program was measured in the number of meals skipped per student, breakfast healthiness, and obesity and overweight rates.

At endpoint, there was no effect of the intervention on breakfast skipping. Nearly 30% of intervention students consumed breakfast foods or drinks from multiple locations, as compared with 21% of control students. A greater proportion of intervention students than control students consumed 100% juice, and a smaller proportion consumed sugar-sweetened beverages and foods high in saturated fat and added sugar.

Many more students participated in free breakfast programs when breakfast was offered in a classroom. This correlated with a higher proportion of students who ate healthier meals in the morning, evidenced by less sugary drinks, lower-fat meals, and more 100% juice. Despite the increase in breakfast at school, the proportion of students who did not eat breakfast only shrunk by around 1%.

There was no difference between intervention and control schools in the combined incidence of overweight and obesity after 2.5 years (11.7% vs 9.1%; odds ratio [OR] 1.42; 95% CI, 0.82-2.44; P = .21). However, the incidence (11.6% vs 4.4%; OR, 3.27; 95% CI, 1.87-5.73) and prevalence (28.0% vs 21.2%; OR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.08-1.89) of obesity were higher in intervention schools than in control schools after 2.5 years.

Source: Effect of a Breakfast in the Classroom Initiative on Obesity in Urban School-aged Children A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial

Surprisingly, despite the quality of breakfast foods, schools in the One Healthy Breakfast program saw an increase in overweight and obese students by almost 10% compared to other schools. Obesity increased in all 16 schools regardless of the breakfast initiative, but schools with classroom breakfast saw a more dramatic increase in obesity on average.

Prior studies have shown that breakfast-in-class programs increase the daily caloric intake of students. While this may be the goal, it is possible that students ate their free breakfast after eating at other locations. Since the rate of students without breakfast did not change dramatically, these students could account for the increased participation. The increase in obesity rate suggests that children already in the overweight category may have a harder time resisting hunger when presented food in class, regardless of if they had eaten earlier.

Final thoughts

Breakfast-in-classroom initiatives are widely thought to be the best way to improve access to nutrition for students in poverty; however, it is clear that access is not the critical barrier preventing children from eating breakfast before school. It is essential to pursue alternative methods to increase

school breakfast program participation without unfavorable

consequences on children’s weight status.