shift work and mental health: Risk of psychological distress based on work schedule

Many adults spend most of their time during the week at work. Employment is essential in our society because it provides us with financial freedom and purpose; not to mention health insurance. An ideal job is one that promotes our financial and psychological growth. However, there are jobs that can actually hurt our health in the long run. An extreme example would be someone who works in a power plant and is exposed to hazardous chemicals regularly. This is a clear health hazard that could result in severe physical distress.

Work and depression

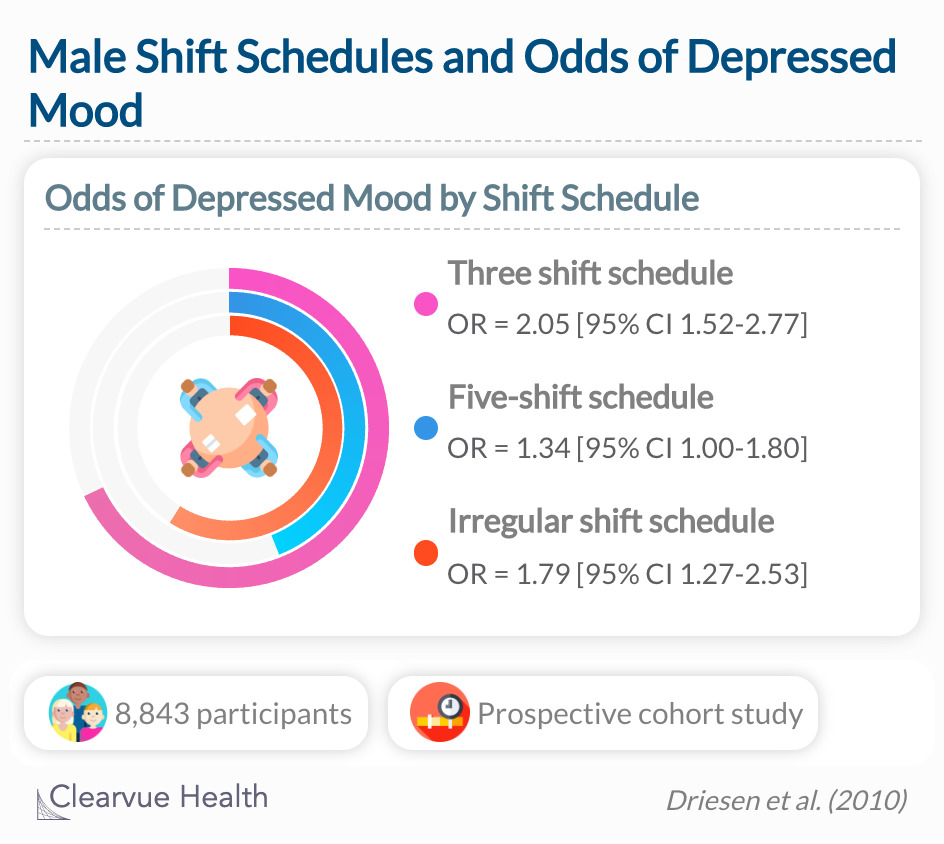

A well-studied health outcome associated with work is depression. A depression diagnosis is a result of more than just a few bad days on the job. Depression can be linked to the constant stressors of the job, and particularly the job schedule. Researchers conducted a study to assess the association between work schedules and depressed mood. Their sample of 8,843 came from the Maastricht Cohort Study. Participants filled out surveys that measured mental health status, working arrangements, and other factors that could mediate the association. The researchers looked at men and women separately.

The odds ratio (OR) for depressed mood was greater for men involved in shiftwork than for men only involved in day work (three-shift OR = 2.05 [95% confidence interval, CI 1.52-2.77]; five-shift OR = 1.34 [95% CI 1.00-1.80]; irregular-shift OR = 1.79 [95% CI 1.27-2.53]). Adjusted for age, educational level, living alone, and long-term illness.

Source: Depressed mood in the working population: associations with work schedules and working hours

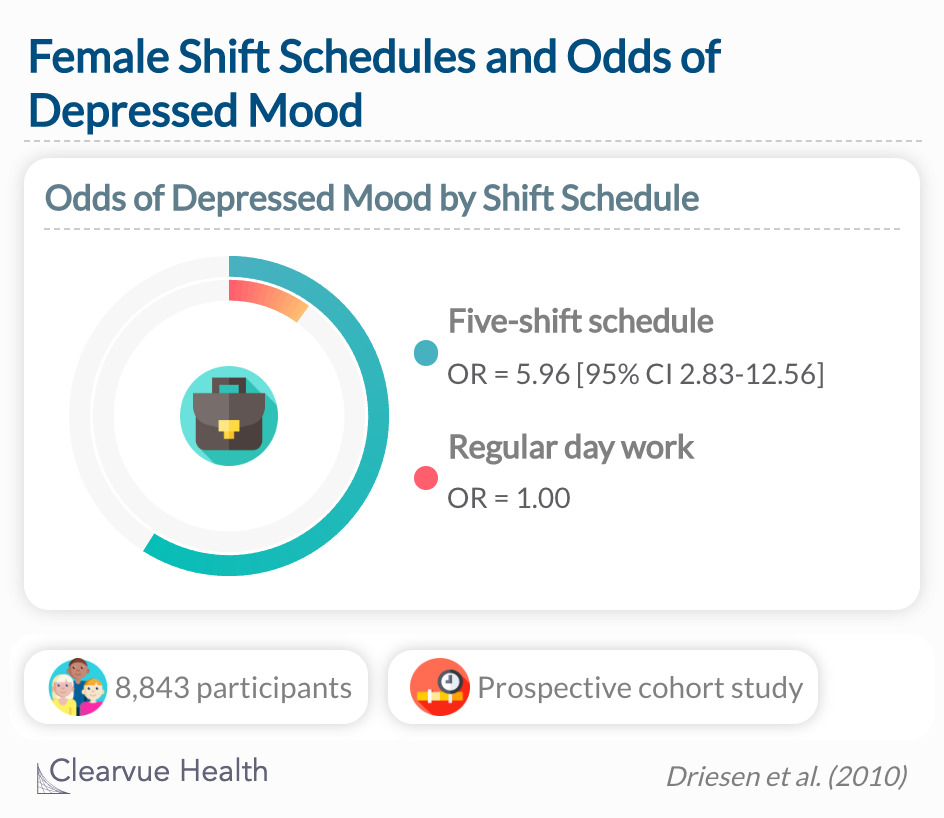

In female employees, five-shift work was associated with a higher prevalence of depressed mood (OR = 5.96 [95% CI 2.83-12.56]).

After analysis, the associations were most significant in male workers as opposed to female workers. Male workers had an increased odds of depressed mood on every shift schedule. Women only had an increased odds of depressed mood on a five-shift schedule. There isn't a clear reason for this difference, however, the sample of women in this study was significantly smaller. A larger sample of women may have been needed to reach statistical significance in the other shift schedules.

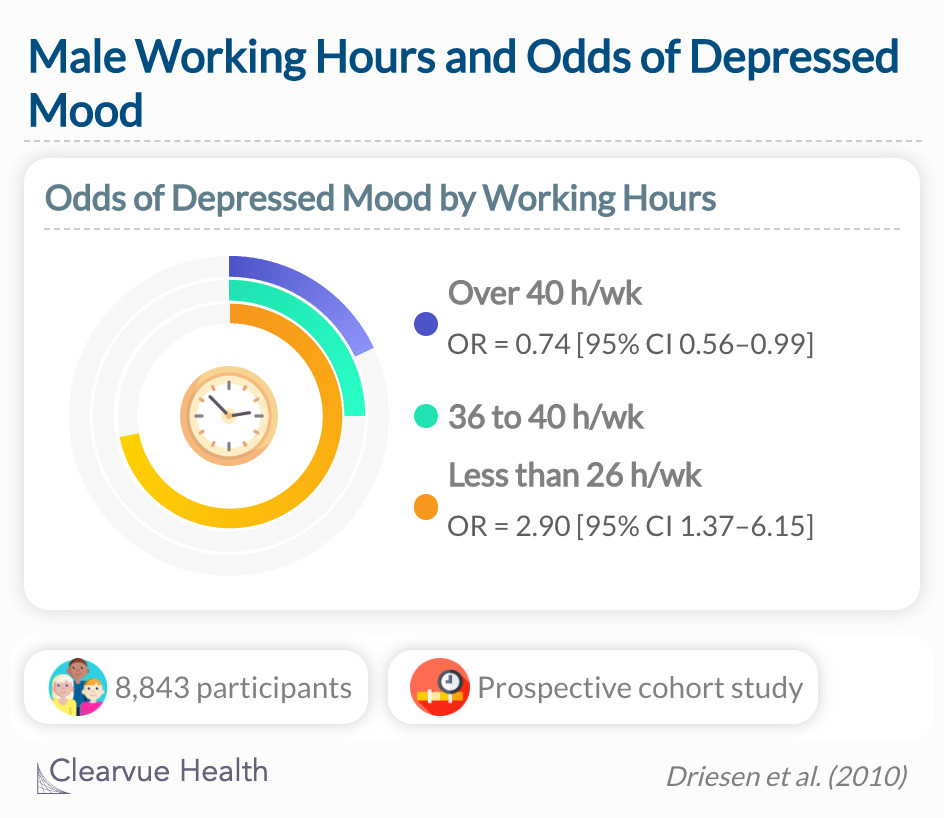

Men working <26 h/wk had a higher prevalence of depressed mood than men working 36-40 h/wk (OR = 2.73 [95% CI 1.35-5.52])

Associations between working hours and depressed mood were much stronger in men as well. Men who worked more than a regular workday had a reduced odds of depressed mood, while men who worked part-time had nearly 3-times the odds of a depressed mood. There are many scenarios that could support these findings. For example, the authors suggested that a proportion of men who work part-time are likely disabled or have a chronic medical illness. This condition in itself substantially increases a person's risk for depression. In this case, the workings hours would not fully explain the association, because chronic illness may be an even bigger factor.

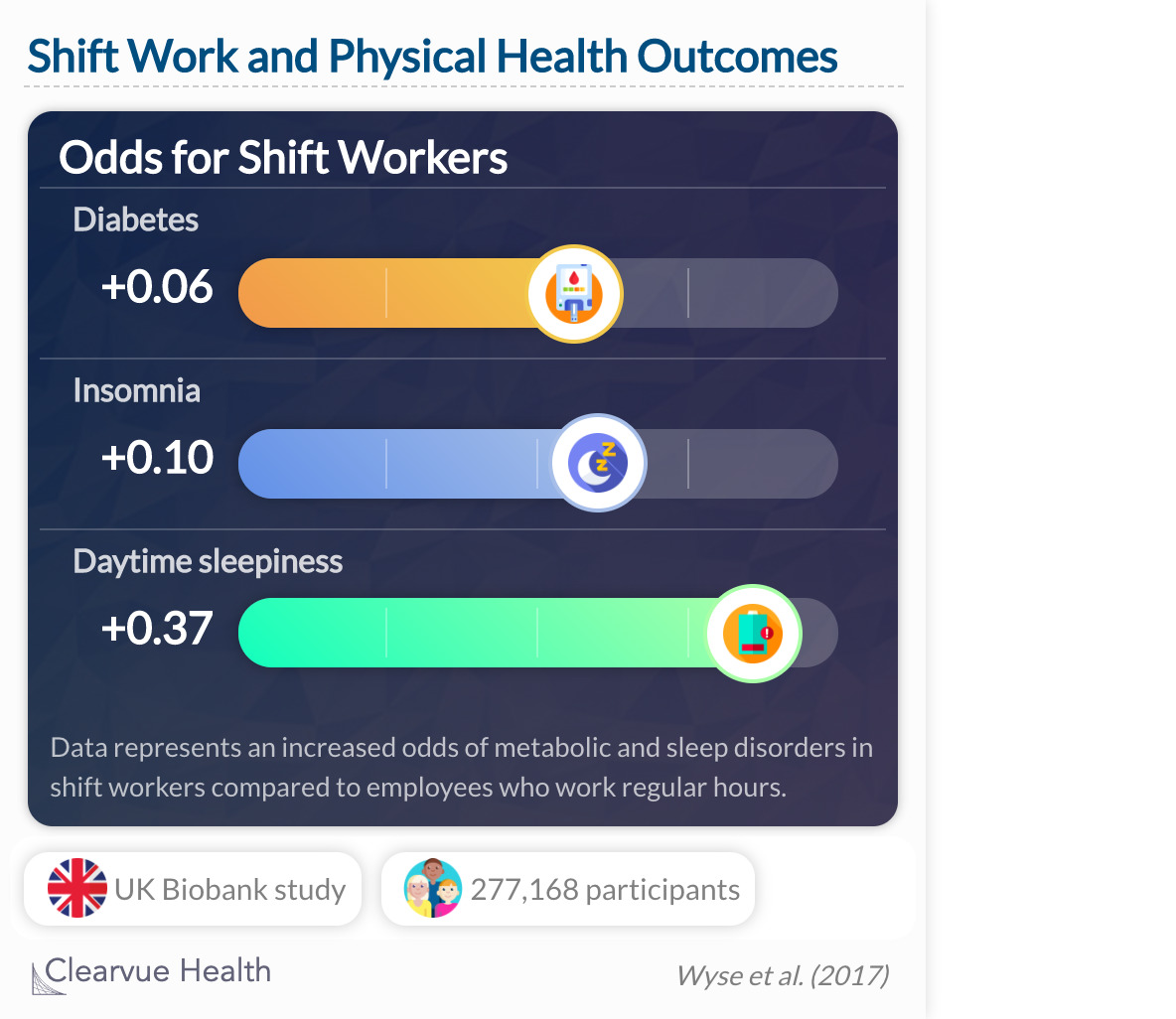

Shift work and physical health

In addition to mental health effects, a study in the UK found significant associations between shift work and physical markers linked to obesity and heart disease. They collected medical and socioeconomic data of 277,168 employed participants from the UK Biobank study. Researchers were particularly interested in metabolic and sleep differences between work shifts.

Shiftwork was independently associated with multiple indicators of poor health and wellbeing, despite the higher physical activity, and even in shift workers that did not work nights.

Source: Adverse metabolic and mental health outcomes associated with shift work in a population-based study of 277,168 workers in UK biobank

The numerical differences in odds are extremely small between shift and non-shift workers. Still, the associations are significant. The margin is so small that the association may become insignificant in a different sample. Regardless, it is important to consider how shift workers may be afflicted by these health conditions. It does make sense that shift workers would struggle with health conditions related to eating and sleeping since they are subject to irregular schedules.

Final thoughts

The social and personal surroundings that lead someone into a job are immeasurable. Workers may have a deeply personal reason for starting or staying at a job. In addition, societal pressures to work and make money are ever-present, especially for men. In a society where everyone is expected to work, whose job is it to consider the mental health of workers? Is it the job of unions, executive boards, or government agencies? The more data on mental health and working conditions that come out, the more evidence we have to implement effective wellness interventions for employees.