sleep, stroke, and disparities: evaluating race, age, and sex

“

Stroke is a disease that affects the arteries leading to and within the brain. It is the No. 5 cause of death and a leading cause of disability in the United States.

American Stroke Association

A collection of quality studies have established an association between sleep and stroke. The evidence claims that those who sleep too little or too much have an increased risk of stroke. However, medicine is not one-size-fits-all. The implications of this association are not the same for every race and sex.

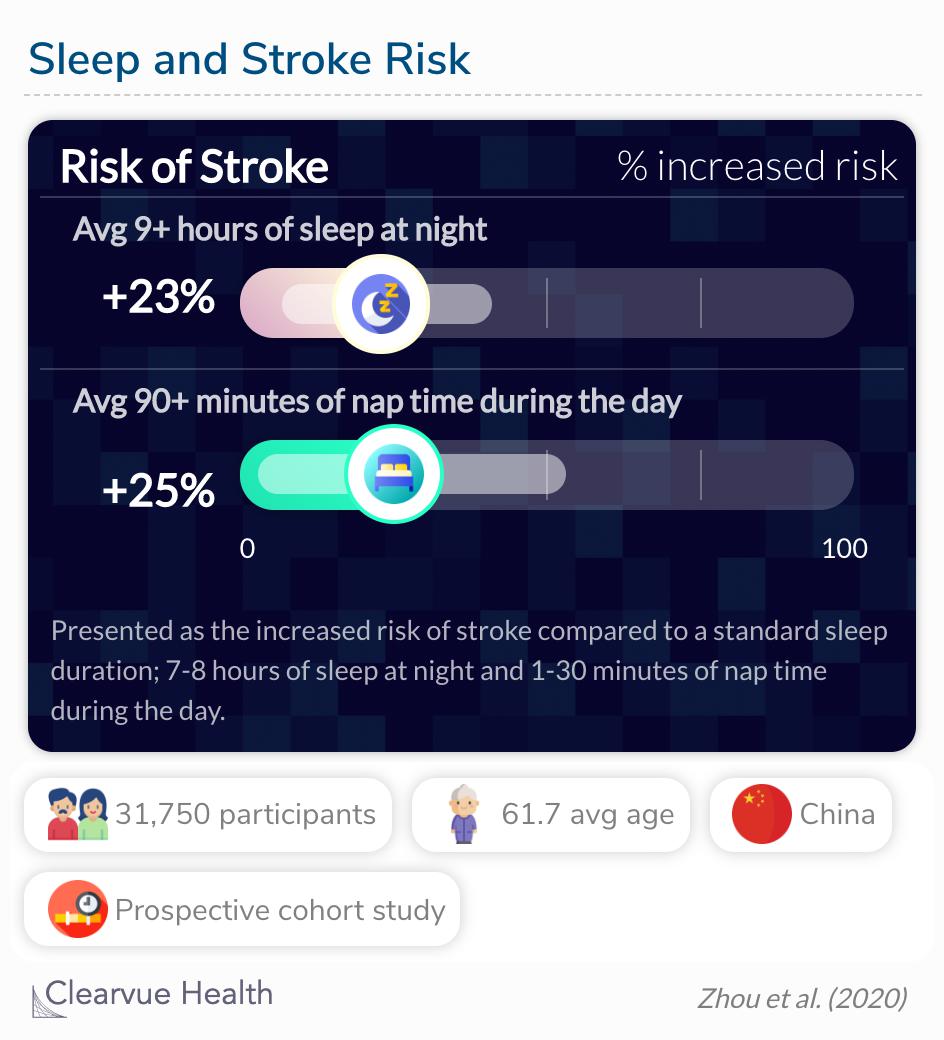

Compared with sleeping 7 to <8 hours/night, those reporting longer sleep duration (≥9 hours/night) had a greater risk of total stroke (hazard ratio [HR] 1.23; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.07–1.41), while shorter sleep (<6 hours/night) had no significant effect on stroke risk. The HR (95% CI) of total stroke was 1.25 (1.03–1.53) for midday napping >90 minutes vs 1–30 minutes.

Source: Sleep duration, midday napping, and sleep quality and incident stroke The Dongfeng-Tongji cohort

Effect of age, sex, and race

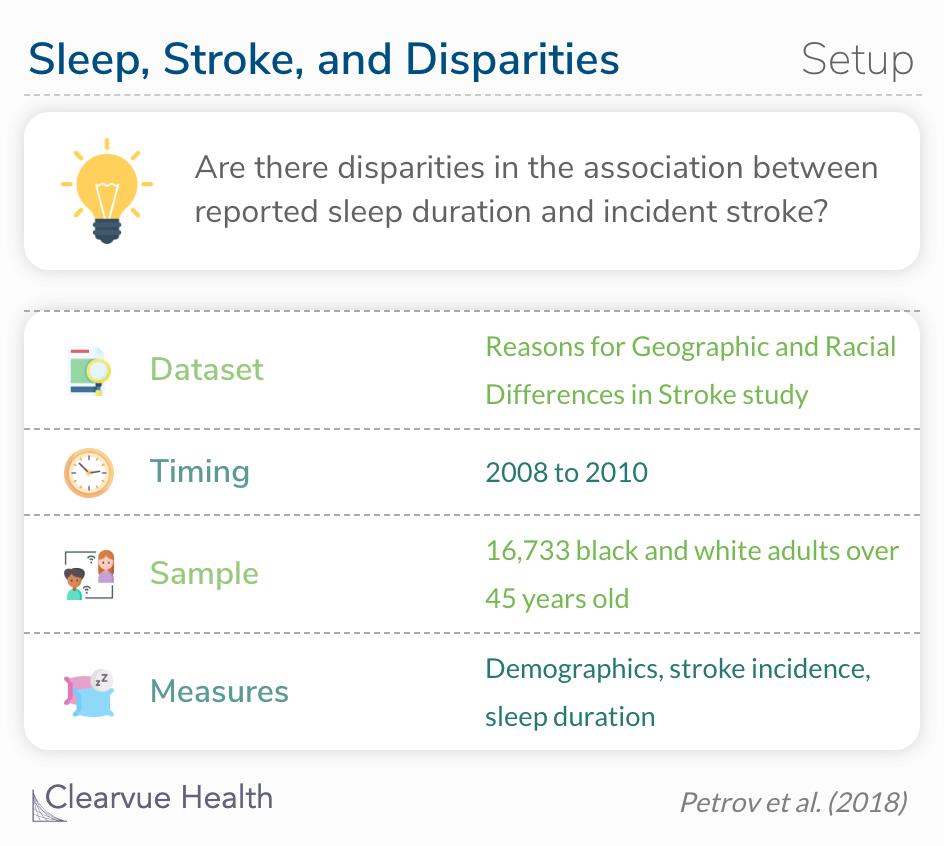

A study was published in Neurology that investigated the association between reported sleep duration and incident stroke in a US cohort of black and white adults and evaluated how race, age, and sex may change the effect. Almost 17 thousand participants released their medical records and filled out surveys about their demographics and sleep habits.

To investigate the association between reported sleep duration and incident stroke in a US cohort of black and white adults, and evaluate race, age, and sex as potential effect modifiers.

Source: Sleep duration and risk of incident stroke by age, sex, and race

Based on reports from the beginning of the study, 10% of the sample were very short sleepers (<6 hours) and 7% were long sleepers (9 + hours). About 37% of the sample were black adults, of which black adults represented 60% were short sleepers and 30% were long sleepers. Over an average follow-up of 6 years, 460 stroke events occurred.

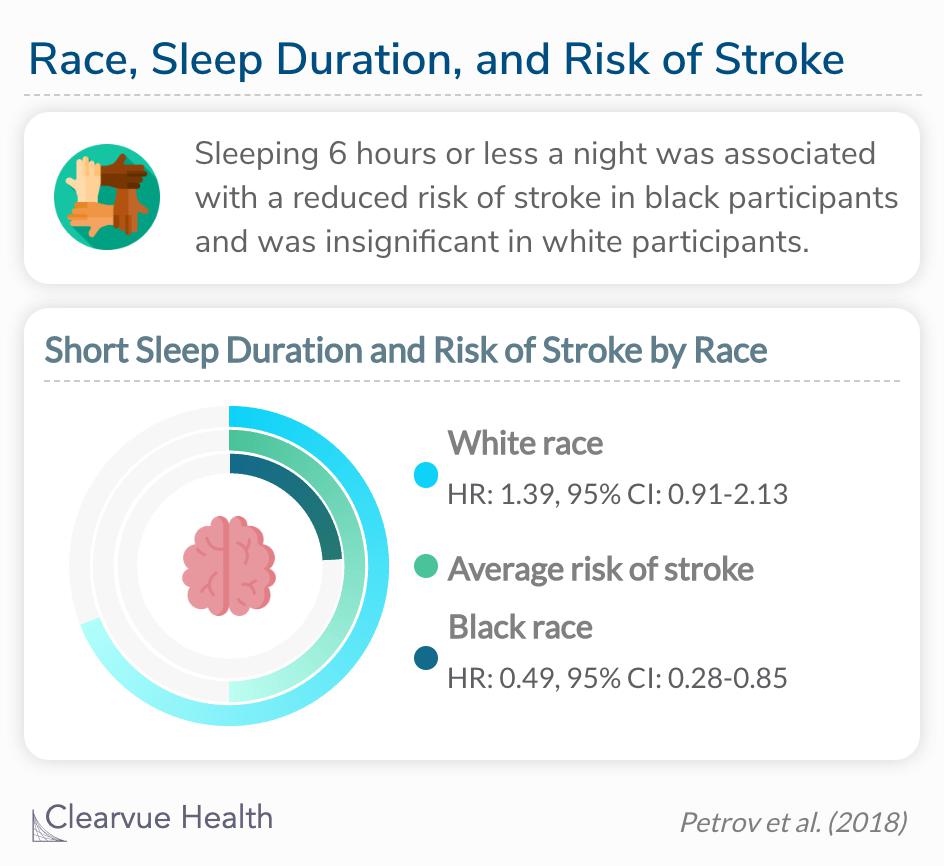

After adjustments, the increased risk for stroke in white participants was attenuated (HR 1.39, 95% CI 0.91–2.13), but the decreased risk for stroke among black participants remained (HR 0.49, 95% CI 0.28–0.85).

The researchers found dramatically different results for black and white participants when measuring the association between short sleep duration and risk of stroke. Black participants who reported a short sleep duration had a decreased risk of stroke, which white participants who reported short sleep duration had an increased risk of stroke. There were no other significant associations between sleep duration and risk of stroke by race; not even for a 9+ hour sleep duration.

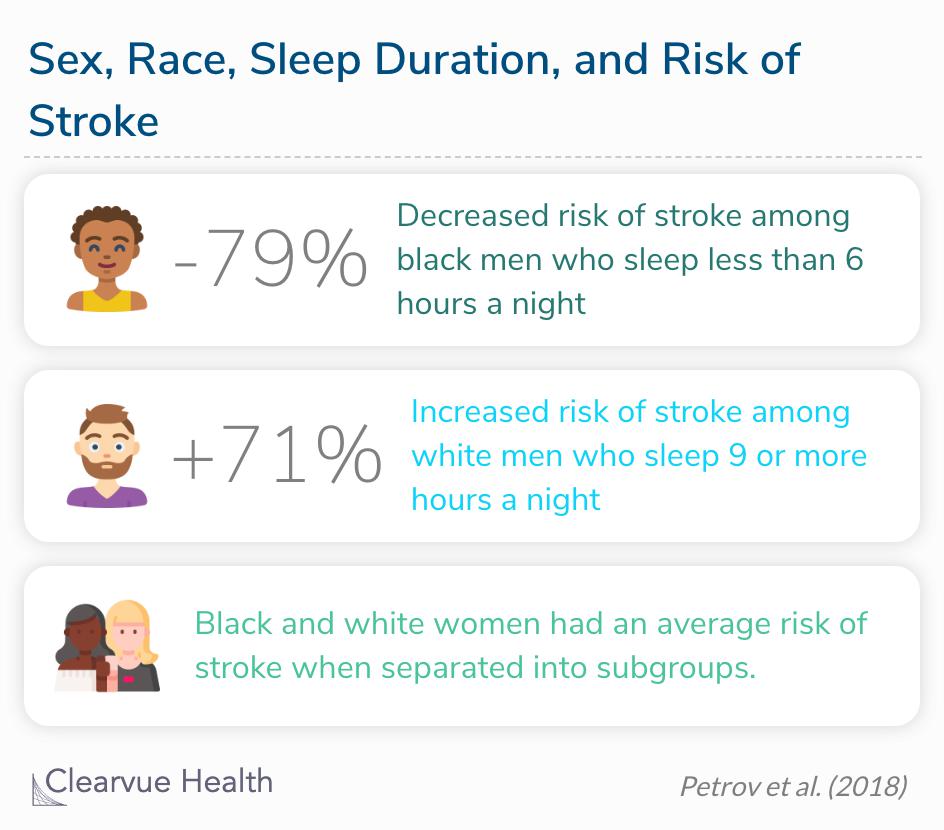

In the stratified demographic model, short sleep duration was associated with decreased risk for stroke in black men (HR 0.20, 95% CI 0.06–0.66) and longer sleep duration was associated with increased risk for stroke in white men (HR 1.96, 95% CI 1.25–3.09). After adjusting for stroke risk factors, the increased risk for stroke in white men (HR 1.71, 95% CI 1.06–2.76) and the decreased risk for stroke in black men remained (HR 0.21, 95% CI 0.07–0.69).

Another analysis stratified the data by both race and sex. In this adjustment, the only significant associations were found in male participants. Taking women out of the black and white samples strengthened the associations. This means that, as a subgroup, white and black women have an average risk of stroke that is not strongly mediated by sleep duration. This specific analysis finally revealed an association between long sleep duration and stroke risk, but only in white men.

Final thoughts

This research is a prime example of health disparities because the impact of stroke risk factors was different by race and gender.