Hyperactivity in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Impairing Deficit or Compensatory Behavior?

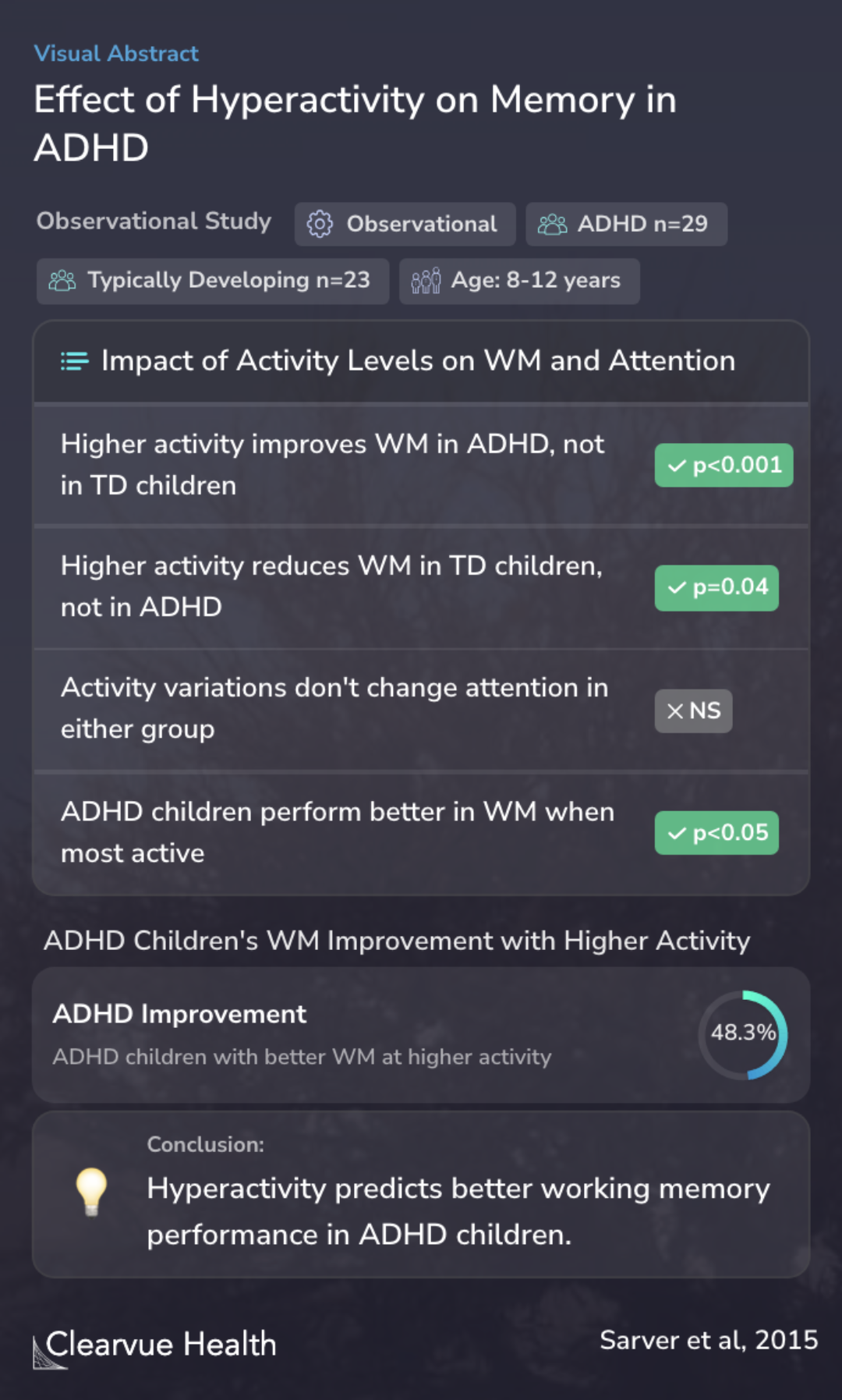

Effect of Hyperactivity on Memory in ADHD

Sarver DE, Rapport MD, Kofler MJ, Raiker JS, Friedman LM

Objectives

The study delves into the idea that too much movement, often seen in kids with ADHD, might not just be a problem but could actually help their brains work better. This challenges the old view that such hyperactivity only gets in the way of learning. In simpler terms, while we usually think being super fidgety might make it hard for kids to focus, this research suggests it could be the opposite for those with ADHD.

Excess gross motor activity (hyperactivity) is considered a core diagnostic feature of childhood ADHD that impedes learning. This view has been challenged, however, by recent models that conceptualize excess motor activity as a compensatory mechanism that facilitates neurocognitive funct...

Methods

The research looked at boys from 8 to 12 years old, some with ADHD and some without, to see how their movement levels connected with their memory and focus during different tasks. They watched these kids closely while they did memory tasks to see how much they moved and how well they did.

The current study investigated competing model predictions regarding activity level's relation with working memory (WM) performance and attention in boys aged 8-12 years (M = 9.64, SD = 1.26) with ADHD (n = 29) and typically developing children (TD; n = 23). Children's phonological WM an...

Results

For kids with ADHD, moving around a lot actually seemed to help them remember things better. But for kids without ADHD, too much movement didn't help and might have even made their memory a bit worse. However, moving more or less didn't really change how well any of the kids could pay attention. I

Analysis of the relations among intra-individual changes in observed activity level, attention, and performance revealed that higher rates of activity level predicted significantly better, but not normalized WM performance for children with ADHD. Conversely, higher rates of activity leve...

Conclusions

So, what this all means is that for kids with ADHD, being hyperactive might be a way for their brains to work better, especially when they need to remember things. This could change how we think about the best ways to help these kids in school or when they learn. We might not always want to keep them still. Plus, this idea fits with other research that says exercise and being active can help kids with ADHD feel and do better.

These findings appear most consistent with models ascribing a functional role to hyperactivity in ADHD, with implications for selecting behavioral treatment targets to avoid overcorrecting gross motor activity during academic tasks that rely on phonological WM.

Key Takeaways

Context

Indeed, other studies echo these thoughts. For instance, a small experiment showed that a 10-week program of regular exercise made kids with ADHD less impulsive and more attentive, with lower anxiety levels. This suggests that staying active isn't just good for the body but also for the brain, especially for those with ADHD.

Moreover, working memory, which is often a challenge for those with ADHD, can actually get better with specific training and therapy. Another study found that kids with ADHD who did special memory training exercises saw a long-term improvement in their memory and ADHD symptoms. This adds weight to the idea that with the right strategies, including physical activity and targeted training, improvements in cognitive functions are achievable for children with ADHD.